MARIF'AH IN THE KALAM OF AL MATURIDI, AL ASHARI AND AHL AL SUFFIYA

Al Maturidi’s view on ma‘rifa (the highest level of knowledge to know of Allah) is based on the human thought and reason. It can be understood either that ma‘rifa can be obtained by the use of merely human reasoning and also that human reasoning is capable of obtaining ma‘rifa. It is reasonable that Al-Maturidi comes to the opinion that everything has its own character of good and bad.

On the contrary, Al-Ash‘ari viewed that ma‘rifa is based on God’s provision and guide. Consequently, good and bad are also decided by Syari (naturally).

Compared to that of Al-Ash‘ari, it is understandable that Al Maturidi’s views on human thought and reasoning seem to fit with Mu‘tazila’s way of thinking. But it does not mean that Al-Maturidi is a Mu’tazili, however. Despite Al-Maturidi’s acceptance of human thought and reasoning that makes him, to some extent, close to Mu‘tazila’s way of thinking, he is still different from Mu‘tazila. It is in this sense, actually that Shaykh Muhammad Abu Zahrah shares his opinion and states that:

“…such is close to the opinion of Mu‘tazila. However, Mu‘tazila followers think that ma‘rifatullah is obliged in mind. The followers of Al-Maturidiyya do not decide such thought, but they think that the obligation of ma‘rifatullah may be found through the fact of mind. This obligation never brings into reality, except Allah, the Supreme One.

The term marifa does not figure in the Quran, [ilm being the term used for knowledge; and Al-Alim, the All-Knowing, is given as a Divine Name, whereas Al-arif is not. Likewise, in the Hadith literature, ilm greatly overshadows marifa. In this regard, two points should be made: first, the notion of ilm in the first generations of

Islam was flexible enough to encompass knowledge both of the contingent domain and the transcendent order. The concept of knowledge at this time, along with a range of other concepts, had a suppleness, a polyvalence, and a depth that was plumbed by the individual in the measure of his spiritual sensitivity: there was no need for a separate word to designate a specifically spiritual kind of knowledge.

Secondly, the Sufis who came to discuss marifa as a distinct form of knowledge were able to quote and interpret certain key verses and ahadith as referring implicitly to the kind of knowledge they were seeking to elucidate.[1] One verse of central importance in this connection is the following:

I created not the jinn and mankind except that they might worship Me. (51: 56)

In his Kitab Al-Luma, Abu Nasr Al-Sarraj (d. 378/988) in common with many other Sufis,[2] reports the comment of Ibn Abbas: the word ‘worship’ here means ‘knowledge’ (marifa), so that the phrase illa li-yabuduni (except that they might worship Me) becomes illa li-yarifuni (except that they might know Me).[3] The very purpose of the creation of man thus comes to be equated with that knowledge of God which constitutes the most profound form of worship. This view dovetails with the hadith qudsi, (a holy utterance by God through the Prophet) so frequently cited by the Sufis: ‘I was a hidden treasure and I loved to be known, so I created the world.’ The word for ‘known’ here is u'raf: ma'rifa thus appears again here as the ultimate purpose of creation in general, a purpose which is realized and mirrored most perfectly through the sage who knows God through knowing himself. For, according to another much-stressed hadith: ‘Whose knoweth himself knows his Lord’-again, the word for knowing is ar'afa. We shall return to this altogether fundamental principle in the final section of this essay. The question that presents itself at this point is why it should have been necessary for the Sufis to adopt the term marifa in contradistinction to ilm, [4] a process that becomes visible from around the third/ninth century.[5] The answer to this question can be stated thus: it was in this period that various dimensions of the intellectual tradition of Islam- theology, jurisprudence, philosophy, to mention the most important—began to crystallize into distinct ‘sciences’ (ulu'm) each of which laid claim to ilm as its preserve, thus imparting to ilm its own particular accentuation and content.[6] What these disciplines had in common was a confinement of the notion of ilm within the boundaries of formal, discursive, abstract processes of thought. For the Sufis to give the name [ilm to their direct, concrete, spiritual mode of knowledge was henceforth to risk associating the spiritual path of realization with a mental process of investigation. This is how Hujwiri expresses the difference between the two types of knowledge:

"The Sufi Shaykhs give the name of marifat (gnosis) to every knowledge that is allied with (religious) practice and feeling (hal) [7] and the knower thereof they call a'rif: On the other hand, they give the name of ilm to every knowledge that is stripped of spiritual meaning and devoid of religious practice, and one who has such knowledge they call alim".[8]

[1] Also, it was held that through mari'fa the less obvious, underlying, and esoteric dimensions of scripture could be grasped. Al-Ghazali (d. 505/1111) writes that the inner meaning of many verses and ahadıth can be understood only through muka'shafa i.e mystical unveiling; muka'shafa is closely connected with marifa, sometimes being synonymous with it and at other times being a path leading to it as the final goal. See F. Jabre, La Notion de la ma'rifa chez Ghazali (Paris: Traditions des Lettres Orientales, 1958), 24–6.

[2] Data Ali Hujweri, Kashf Al-Mahjub p. 267, and Qushayri (d. 465/1074) in his famous Risala, trans. by B. R. von Schlegel as Principles of Sufism (Berkeley, Calif.: Mizan Press, 1990), 316.

[3] R. A. Nicholson (ed.), Kitab Al-Luma (London: E. J. Gibb Memorial Series, 22, 1963), Arabic text, 40.

[4] It would be wrong to say that this process was either uniform or unilateral. The two terms were frequently to be found as synonyms within Sufi texts; sometimes marifa would be described as a form of ilm, and vice versa; and there was no unanimity on the question of marifa being superior to ilm. See Kalabadhi’s (d. 385/995) Kitab Al Ta'arruf li madhhab Ahl Al-tasawwuf: The Doctrine of the Sufis, trans. by A. J. Arberry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1935), ch. 22, Their variance as to the nature of gnosis’. For the use of the two terms as synonyms, see Abu Sa'id Al-Kharraz’s (d. 286/899) Kitab Al-Sidq: The Book of Truthfulness, trans. A. J. Arberry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1937), 49–50, Arabic text, 60. Also it should be noted that even the Sufi most frequently cited in connection with the first formal articulation of ma'rifa. D'hul-Nun Al-Misri (d. 245/859), speaks of the marifa of the common folk, and that of the [ulama], and that of the saints. See Farıd Al-Din Attar’s Tadhkirat al-Awliya], ed. R. A. Nicholson, (London: Luzac, 1905), part 1, Persian text 127. Finally, regarding the question of which is superior, ma'rifa or ilm, Ibn Al-Arabi writes that the apparent disagreement is only a verbal one: it is the selfsame knowledge of the supernal verities that is in question, whether this be called ma'rifa or ilm. See W. C. Chittick, The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn Al Arabi’s Metaphysics of Imagination (New York: State University of New York Press,1989), 149

[5] One can find, prior to this time, scattered references to the term in a specifically Sufi context. For example: Ibrahim bin Adham (d. 160/777) is said to have developed the notion of ma'rifa (M. Smith, An Early Mystic of Baghdad: A Study of the Life and Teachings of Harith bin Asad Al Muhasibi (London: Sheldon Press, 1935), 73. The lady Umm al-Darda], a traditionist of the first century Hijra, was reported as saying, ‘The most excellent knowledge (ilm) is the gnosis (al-marifa)’ (cited in Franz Rosenthal, Knowledge Triumphant: The Concept of Knowledge in Medieval Islam (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1970), 139).

[5] One can find, prior to this time, scattered references to the term in a specifically Sufi context. For example: Ibrahim bin Adham (d. 160/777) is said to have developed the notion of ma'rifa (M. Smith, An Early Mystic of Baghdad: A Study of the Life and Teachings of Harith bin Asad Al Muhasibi (London: Sheldon Press, 1935), 73. The lady Umm al-Darda], a traditionist of the first century Hijra, was reported as saying, ‘The most excellent knowledge (ilm) is the gnosis (al-marifa)’ (cited in Franz Rosenthal, Knowledge Triumphant: The Concept of Knowledge in Medieval Islam (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1970), 139).

[6] The presumption by others of ilm as a technical term prevented the Sufis permanently from selecting ilm for employment as one of the numerous technical terms of their own vocabulary and from using it to designate by it one of their specific states and stations. Since ma'rifa and yaqin lent themselves without much difficulty to doubling for ilm, they were indeed widely substituted for it (ibid. 165). 13 See V. Danner, ‘The Early Development of Sufism in S. H. Nasr (ed.), Islamic Spirituality (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987), i. 254.

[7] This should be translated as ‘spiritual state’. The word ‘feeling’ is far too vague a translation of hal.

[8] Kashf Al-Mahjub, 382. Much the same is said by Qushayri in his Risala, in the chapter titled Al- Marifatu bi-Llah’, 316.

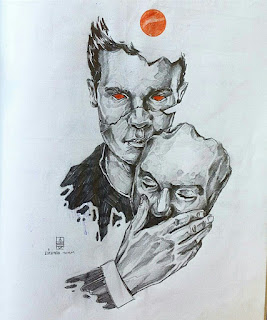

[Pic of a believer seeking Intercession in the shrine of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya (RA)]